- Home

- Paul Southern

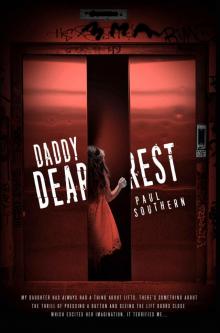

Daddy Dearest

Daddy Dearest Read online

Copyright © 2015 Paul Southern

Paul Southern has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, copied in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise transmitted, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other non-commercial uses permitted by copyright law, without written permission from the author.

This novel is a work of fiction. Names and characters are the product of the author’s imagination and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Cover design by Darren Cocks

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

About the Author

Also by Paul Southern

Reviews

1

The thing I hate about flats is the people in them. It’s not that I’m necessarily misanthropic by nature; it’s just I don’t like the noise. I don’t like any noise. Above me, below me, to my left and right, the chances of it increase exponentially when I’m in my flat. Whether it’s the woman upstairs, banging nails down on her laminated floorboards with her six inch stilettos (I measured them once), or the fat Greek next door, coughing and exploding in his bathroom, or the thump of music reverberating up the concrete walls from the two fags below, there is the inescapable immersion in noise. For a while, it only used to bother me at odd moments; but that was when I had a life. Now that it’s gone, all I have left is the countdown to the next thump, cough, footstep, water-pipe, door being banged, which will set me off.

Flats bring out the worst in people; all their selfishness and fuck thy neighbour attitude is magnified there. You are reliant on their better natures, their compassion, their understanding - their civility - and those are traits you’d have trouble finding in a church, never mind an apartment. Flats bring out the very worst in people: me, more than most.

A few years ago, I lived in a block in the suburbs. It was one of those flat-roofed seventies affairs which were all the rage at the time: the way of the future. Now, it’s nothing more than a hunk of dilapidated concrete, brittle and hollow like a drum. When someone on the top floor played music, it shook the whole block. I had two black girls playing it. Now, don’t get me wrong, I’m as PC as the next guy, but there’s something about them that’s not right; they look at the world differently. And they’re loud: like really loud. Every Friday and Saturday they invited their underclass mates over to party. When I wrote them a polite letter complaining, they kicked my door in. Now, I’m not big on fighting: I never have been. I’m one of those that run. Flight or fight is more than a missing L: I want to live. So I did - with a bang. I’m not saying it was the right thing to do. I’m just telling you.

I’d moved my stuff out on Friday and given the management company my notice. I like to do things properly. I even offered to pay the next month’s rent, though they had loads of people on the waiting list who’d have paid it for me. It may not have been the best place to live, you see, but it certainly wasn’t the worst. If it wasn’t for the black girls, it may even have been a nice place. But, it only takes one, doesn’t it? Or two.

I left all my stuff at a friend’s - I didn’t have much; just the records and books I’d collected the last forty-two years: nothing really important - and went back. I had my key till Monday. I could hear the music from upstairs before I even got inside. I was scared, of course - I always am - but I was pissed off, too. I looked at the new door the management company had stuck on - despite my largesse, they tried charging it to me - and sat in my flat and listened to the heavy footsteps on my old roof, and after a while, guess what? They ceased to bother me. They became part of the city’s general thunder. You see, I was free. I could finally see it the way other people did, as somebody else’s problem. The flat was no longer mine.

At 11.30, I got myself ready. I’m not saying I intended to do any real harm, but I’d be lying if I said I didn’t think about it. Powerless people fantasise about revenge all the time; it’s one of my specialities. So I went up to their floor. Luckily, no one was in the corridor. I stared at their lovely, unmarked door for a few minutes, then opened the electricity box next to it. These old flats had a little cupboard outside with the meter in. Gas would have been better, but you get what you’re given, don’t you? I knew I only had a few seconds. I took out the key the guy who put my door on left me. You’d be surprised what people will do when you put things to them. He gave me a fascinating account of cams and cylinders and plugs, and how easy it was to unpick dead-bolt locks; there was no lock he couldn’t master. When I said I had no intention of breaking in anywhere, he looked mightily relieved.

‘No,’ I told him. ‘I want to lock people in.’

Now, his demeanour changed at that point, but not to the point of ending the conversation. As he polished the wood around the frame of my door, and blew the dust on to the floor, I knew I had him.

‘I just want to borrow it,’ I said. ‘I’ll return it on Monday.’

The key slipped into the lock, the bolt slid into place, just like he said it would. The music was so loud, the jamb shook. I took out another key, an old mortise I never used, and turned it in the lock. I felt the metal bend. You weren’t going to force that from the inside. Then I threw the master switch by the meter.

All went quiet and dark. I took the strip light out above me and listened. For a moment there was nothing. Then it all exploded. There were shouts and screams from inside. I heard people coming down the hall, trying the door, then aggressive shoves and kicks as they realised it was jammed. The girls were there, too. I recognised their guttural slang and smiled. I felt tempted to say something, but, as I say, I’m not one for fighting. I only stayed there a minute, just to make sure there was no way out, then returned to my flat. Everything was in order.

At 11.40 I locked up and left. The block of flats backed onto a field which bordered a railway line. A passing freight train trundled by as I ran. The moon was hidden behind a cloak of thick cloud. I looked up at the third floor, at the blacked out windows above mine, and lit the bottle in my hand. It was the only visible light for hundreds of yards - a flare for help, a firecracker of hate. I traced its flight as it headed for the window and then ran into the trees. I didn’t look back. I imagined a beacon being lit along the watch-towers and, shamefully, two black girls burning on top. Like I said, me more than most.

Later that month, I moved into the Sears building in the centre of town. It was an old Victorian warehouse redesigned for the times: eight storeys high, the pick of the city’s ‘new’ architecture, with high ceilings and glass fronts and space to breathe. Lots of media people lived there: gays: bohemians. As far as I could tell,

there were no black girls, and certainly no underclass types, although I could see them when I looked outside, scavenging for cigs and drugs, staring at the gutters and pissing against the walls. I saw the rivers of it snaking down the road in the mornings, the stains on the stones, the smell of alcohol and the packets of condoms and dirty needles. I tried to explain it all to my five-year-old daughter when she splashed through the pools and held her nose and told me how disgusting it was. I told her not to get her shoes wet because she’d splash it on her tights. She held my hand and looked down like there were monsters in there and asked me to lift her up and I did. For your five-year-old girl, you’ll do anything.

I haven’t spoken to you about her before. I’m just getting round to it. I have to put her in context first, so you understand. If you ever do.

2

My daughter has always had a thing about lifts. There’s something about the thrill of pressing a button and seeing the lift doors close which excites her imagination. It terrifies me. Every time she walks in, I imagine it’s the last time I’ll see her. What if she hits the button before I get there? What if the lift doors close and I can’t get her out? It drives me nuts. There are eight floors in the Sears building, nine if you count the basement, and the lift is fast: more like a fairground ride, really. It does top to bottom in twelve seconds. I’ve timed it. Taking the stairs, I’ve done it in forty-two. That leaves a gap of thirty seconds. You’d be surprised what can happen in that time. I was.

In the lobby, she looks up at me with that smile on her face, her little teeth glowing white, and I know what’s going through her mind. She wants to press every button, but knows I’m going to get cross if she does. It’s a terrible bind. The thing you enjoy most is the thing you can’t do. Sometimes, I feel like telling her she can press the lot, in any order; just do what she wants. If the lift gets stuck and we can’t get out, I’ll be able to teach her an important life lesson. Now look what you’ve done. We’ve got stuck. What are we going to do? For a few seconds, she’ll be quiet, then she’ll settle down and say it was me. She’s already getting that female thing, the art of deflecting blame. I’m not sure who learns most out of these little battles: me or her. It certainly tests my patience more. It tests my anger management, my anxiety levels and my blood pressure. Whatever I do, I’m going to lose.

I wish I was like those underclass types sometimes, and didn’t care what people thought. They give their kids a good hiding, the way my father gave me, the way his father gave him, an ad hoc solution to all life’s problems: leather ’em; teach ’em. But I’m too conscious of other people’s opinions. I look at my little girl and hope she’s going to behave herself. I don’t expect it. I don’t expect anything, really. Just the formalities: the hellos, the how are yous, the isn’t the weather nice calm of ordinariness.

I can’t do that in the flat. Nice and calm are not on the agenda. When she comes to stay at the weekends, the noise levels hit the roof - literally. At the weekends, I become the noisy neighbour, and it makes me guilty as hell. She bangs things, throws things, sings at the top of her voice, plays on the computer with the volume turned up maximum, and runs through the apartment, forgetting that the doors aren’t hung properly - as I’ve tried to explain to her a million times before - and don’t just bang: they SLAM. She looks up at me and smiles and she can’t tell that I’m being serious and that I’m actually quite upset. That will come when she’s older, if it comes at all.

The thing about all the noise is that it compromises me: I can hardly complain about the bangs and bumps and music during the week if I’m making such a racket at weekends, can I? I can’t just say, yes, but it’s my daughter. They’ll say, well, have you no control over her? Then what will I say? I don’t.

No one has shown any sign of complaining yet, anyway. In fact, they may never do. You see, if anything, my daughter has become quite a boon to me at weekends. Everyone smiles at me when I’m with her. Actually, that’s not quite true; they smile at her. The middle-aged tart next door does that a lot. She looks at her, then looks at me. I guess she’s sizing me up, wondering how I got here, who the girl is, where her mum is; all the kinds of things that go through my head when I meet people. How did they get to be here? Are they happy? Most of them look it. She looks it. She has a pleasant, maternal face that makes me think of country women, the kind that bakes bread and sit all day in the kitchen with apples in their cheeks. She’s a strawberry blonde and lives on her own. She has had a lot of male visitors. Some of them look a bit unsavoury; I’ve peered at them through the keyhole, overheard their conversations when they’re in bed (her bedroom backs on to my bedroom), when she’s making love. I can live with that kind of noise.

When my daughter and I leave the flat, I feel kind of special. I use her terribly. I buy her everything, give her fireman’s lifts, play games with her, take her to the cinema, so that she gives me a sprinkle of her magic fairy dust. It transforms me from the balding, middle-aged man I am into a loving father, and that is the quality I have discovered all women admire. They smile at me, maybe compare me to their own husbands and boyfriends. Even the young, pretty ones do - the ones who could, in fact, be my daughter. My daughter puts me back in the frame, back in the picture. The sexual instinct doesn’t die; it does what it has to to survive. Just like we do. I bathe in my daughter’s reflected glory for that very reason - am given life merely by association with her - so I can smile and laugh and acknowledge the world and show myself off again - to say to women that I am still here.

‘Don’t press that button.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because we’re not going down. We’re just putting the rubbish down the chute.’

‘I want to.’

Cue the smile.

‘I want to go to Minus One.’

Minus One is the basement, where the bins are kept.

‘We haven’t got time, darling.’

I turn quickly and her finger is on the button. She’s daring me.

I point mine.

The bell rings and the lift opens behind her. She looks at me as if to say it wasn’t her. I take the rubbish in and hold her hand. The doors shut behind us. They take two seconds to close.

It’s a warren down there, a maze of concrete and steel. Doors open at every twist and turn. My daughter tries every one. I look at the signs outside, the red triangles with danger of electrocution, danger of death, stamped on them, and try to explain: you don’t go in there, you could kill yourself. She understands this now. She knows the difference between being here and not. It frightens her as it frightens me, a shadow which will not go away. I know my wife tried to make her feel better by giving her all the heaven stuff, but I thought it was better to be honest. I told her flatly: I don’t know. No one does. She’s reconciled to that now, although she still gets upset.

I know she thinks about it. When I read her a story at night and the prince or princess is faced with death, I know she’s looking down the long lens of her own life. I want to spare her that at the same time I want to prepare her for it. That’s what those Grimm’s stories are all about, anyway; getting you used to the inevitable. The ‘lived happily ever after’ scenarios were tagged on to make them more palatable. Children know that. It’s us adults that insist on deluding them.

‘Do princes and princesses die?’

I look at her face and want to hold her.

‘Yes, darling.’

‘Will you die?’

‘Yes, darling. Everyone does.’

‘I don’t want to die.’

I know what she means.

‘Don’t go near those doors, then. Stay with me.’

It feels like we’re in the bowels of a ship, with those huge metal pipes overhead, pumping steam and water into the turbines, and the electricity generator humming through the walls. Somewhere far above us, a toilet is flushed, or a bath is emptied, and water becomes Niagara all around us. Everything is magnified: our footsteps, our voices. They echo round the corridors

, doubling back on us, deafening us. I know why she likes it down here and can’t blame her for wanting to come. It’s an adventure playground. To me, it’s more. Every time I take her here, I think it. We’re in a subterranean netherworld and I am Orpheus, not daring to look back. Behind me, she is Eurydice, and I am listening for the soft fall of her feet, hoping and praying - yes, praying - that she’ll be there when we’re out.

The bin bag swings in my hand. It’s not a real bin bag, just a knotted Tesco bag. I’ve downscaled since living on my own. I look at the mouldy banana my daughter has just thrown away and the tea bag on top.

‘Do you want to do it?’

She smiles and skips to the double doors behind which the bins are kept. She hasn’t the strength to push them open - they’re those big fire doors - but sometimes one has been left open. This is her favourite place. There are two large chutes which hang over a steel wheelie bin at one side. The room is littered with other Tesco bags which have trampolined off the top on to the floor. They are split and also contain bananas and tea bags. I don’t know why the cleaners or caretakers don’t change the bins more regularly. They fill up every two days. Two other steel wheelie bins are parked on the far wall, empty. I peer in. My daughter is kicking through the rubbish on the floor.

‘Do you want a ride?’

She smiles and says yay at the top of her voice. I pick her up and drop her into one of them.

‘Close the lid.’

‘You won’t be scared?’

She shakes her head.

I wheel her round for a bit, making stupid giant noises. She giggles and bangs on the side saying I can’t find her and I, like an idiot, tell her the same. I, who can’t find it in me to tell her a lie about dying, go along with it. But that’s because it’s a game, isn’t it? You can tell lies in a game. That’s why we play them. Now you see her, now you don’t.

Daddy Dearest

Daddy Dearest